Using Reinforcement Learning for Variational Inference

Published:

This blog post details how we can use ideas from Reinforcement Learning (RL) to efficiently perform variational inference in sequential settings.

Sequential Variational Inference

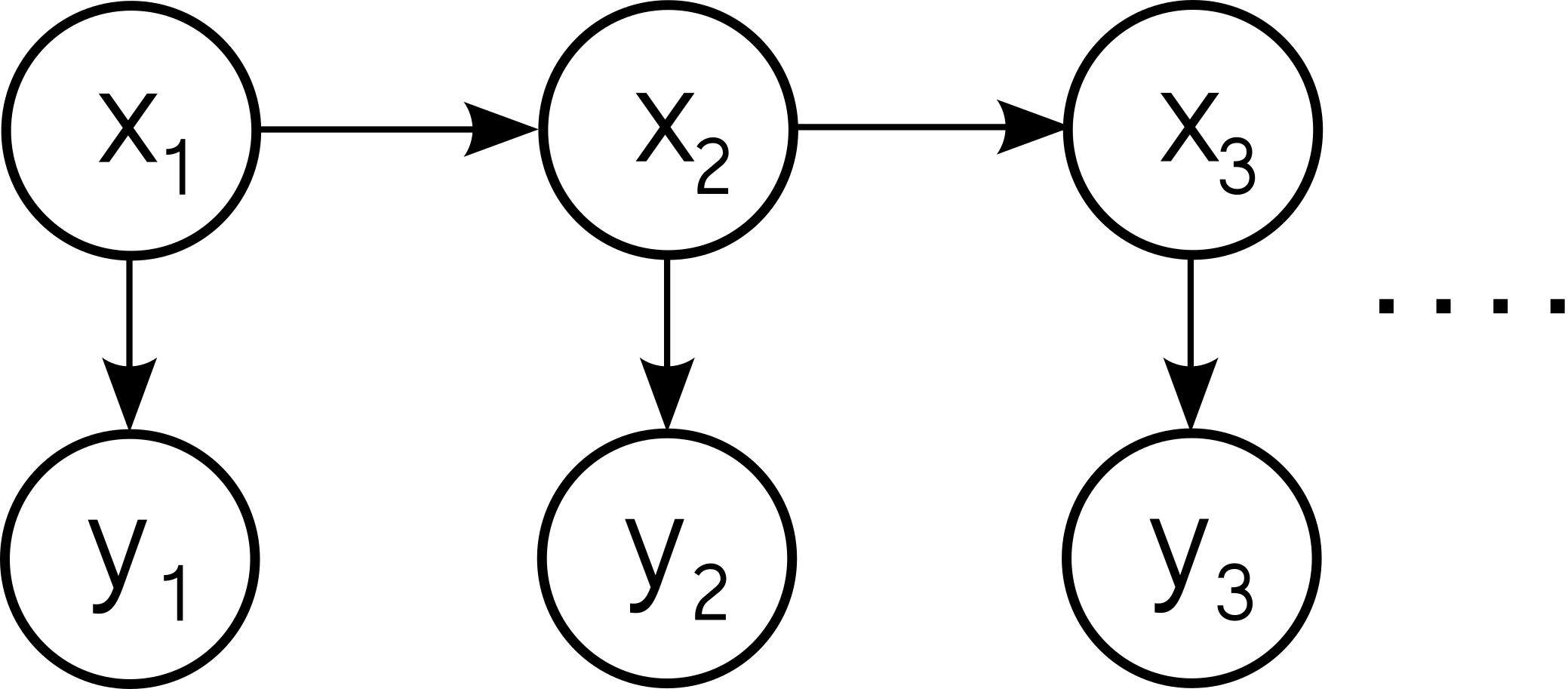

We will be modelling sequential data in the form of a series of observations \(y_1, y_2, \dots, y_T\). We assume that there is some hidden true state of the world \(x_t\) that is producing these observations and undergoing some form of transition between each time step. This is summarized in the following graphical model.

To define the model, we decide on an observation distribution

\[y_t \vert x_t \sim g(y_t \vert x_t)\]and a transition distribution

\[x_{t+1} \vert x_t \sim f(x_{t+1} \vert x_t)\]This defines a joint distribution over hidden states and observations

\[p(x_{1:T}, y_{1:T}) = \prod_{t=1}^T f(x_t \vert x_{t-1}) g(y_t \vert x_t)\]We would like to make inferences about the hidden state given we have seen the observations \(y_1, y_2, \dots, y_T = y_{1:T}\). That is, we would like to reason with the posterior distribution

\[p(x_{1:T} \vert y_{1:T})\]This posterior is intractable to compute directly in most cases which is where variational inference comes in handy. Using the variational inference framework, we create a variational distribution \(q^\phi(x_{1:T})\) with parameters \(\phi\) that will approximate this true posterior distribution for a given set of observations \(y_{1:T}\). We perform this approximation by maximizing the evidence lower bound (ELBO) with respect to \(\phi\)

\[\text{max} \quad \text{ELBO}_T\] \[= \text{max} \quad \log p(y_{1:T}) - \text{KL} \Bigg( q^\phi(x_{1:T}) \vert \vert p(x_{1:T} \vert y_{1:T}) \Bigg)\] \[= \text{max} \quad \mathbb{E}_{q^\phi(x_{1:T})} \left[ \log \frac{p(x_{1:T}, y_{1:T})}{q^\phi(x_{1:T})}\right]\]This corresponds to posterior approximation as the data log likelihood \(\log p(y_{1:T})\) does not depend on the variational parameters \(\phi\) so maximizing the ELBO corresponds to minimizing the KL divergence between the variational distribution and the true posterior.

Line of attack for online sequential variational inference

The ELBO maximization approach works well when we have a fixed number of observations \(y_{1:T}\). However, what happens if we continually receive new observations and wish to perform inference after we receive each one i.e. we would like to approximate \(p(x_{1:T} \vert y_{1:T})\) and then \(p(x_{1:T+1} \vert y_{1:T+1})\) and then \(p(x_{1:T+2} \vert y_{1:T+2})\) and so on.

To do this, we will make use of a factorization of the true posterior distribution. This factorization will allow us to only update our approximation without needing to re-approximate all terms from \(1\) to \(T\). The factorization is

\[p(x_{1:T} \vert y_{1:T}) = p(x_T \vert y_{1:T}) p(x_{T-1} \vert x_T, y_{1:T-1}) p(x_{T-2} \vert x_{T-1}, y_{1:T-2}) \dots p(x_1 \vert x_2, y_1)\]Notice how each factor, \(p(x_k \vert x_{k+1}, y_{1:k})\), only depends on observations up to time \(k\) and not on future observations \(y_{k+1:T}\). This is because it is conditioned on \(x_{k+1}\) and this hidden state summarizes all future information. The future observations hold no extra information about the distribution over \(x_k\). This is significant because we can approximate \(p(x_k \vert x_{k+1}, y_{1:k})\) with \(q^\phi(x_{k} \vert x_{k+1})\) at time \(k\) and then hold it constant at future time steps. The true factor does not depend on future observations, and so we do not need to update our variational factor at future time steps.

Using this factorization, we will perform variational inference with the following variational distribution

\[q^\phi(x_{1:T}) = q^\phi(x_T) q^\phi(x_{T-1} \vert x_T) \dots q^\phi(x_1 \vert x_2)\]When we move to the next time step, we will re-use all the variational factors \(q^\phi(x_{T-1}\vert x_T) \dots q^\phi(x_1 \vert x_2)\) and just add on \(q^\phi(x_{T+1}) q^\phi(x_{T} \vert x_{T+1})\) to the front. We have now reduced the computational work load to just having to optimize two variational factors, however, we still need to decide on our objective. Simply plugging the variational distribution specified above into the ELBO gives

\(\text{ELBO}_T = \mathbb{E}_{q^\phi(x_{1:T})} \left[ \log \frac{p(x_{1:T}, y_{1:T})}{q^\phi(x_{1:T})}\right]\) \(\text{ELBO}_T = \mathbb{E}_{q^\phi(x_T) q^\phi(x_{T-1} | x_T)} \left[ \log \frac{f(x_T \vert x_{T-1}) g(y_T \vert x_T) q^\phi(x_{T-1})}{q^\phi(x_T) q^\phi(x_{T-1} \vert x_T)} + \mathbb{E}_{q^\phi(x_{1:T-2} \vert x_{T-1})} \left[ \log \frac{p(x_{1:T-1}, y_{1:T-1})}{q^\phi(x_{1:T-1})}\right]\right]\)

The problem occurs with this term in the objective which contains many terms from \(1\) to \(T-1\):

\[\mathbb{E}_{q^\phi(x_{1:T-2} \vert x_{T-1})} \left[ \log \frac{p(x_{1:T-1}, y_{1:T-1})}{q^\phi(x_{1:T-1})}\right]\]The variational distribution \(q^\phi(x_{1:T-1})\) contains only fixed factors and so the term inside the expectation does not contribute directly to objective gradients for the new factors \(q^\phi(x_T)\) and \(q^\phi(x_{T-1} \vert x_T)\). However, this term depends on \(x_{T-1}\) which does depend on the new factors because \(x_{T-1}\) is being sampled from \(x_{T-1} \sim q^\phi(x_T) q^\phi(x_{T-1} \vert x_T)\). Therefore, this term will contribute to the gradient of the objective and cannot be ignored. We need a way to avoid having to directly calculate this term as it requires stepping all the way back through from \(T-1\) to \(1\) every time step. In other words, we would like an objective with only a constant number of terms and whose cost to evaluate does not grow with time.

We will now see how we can use ideas from Reinforcement Learning to accomplish exactly this.

Reinforcement Learning

Before showing how we can use RL in our setting, I will first summarize some of the basics.

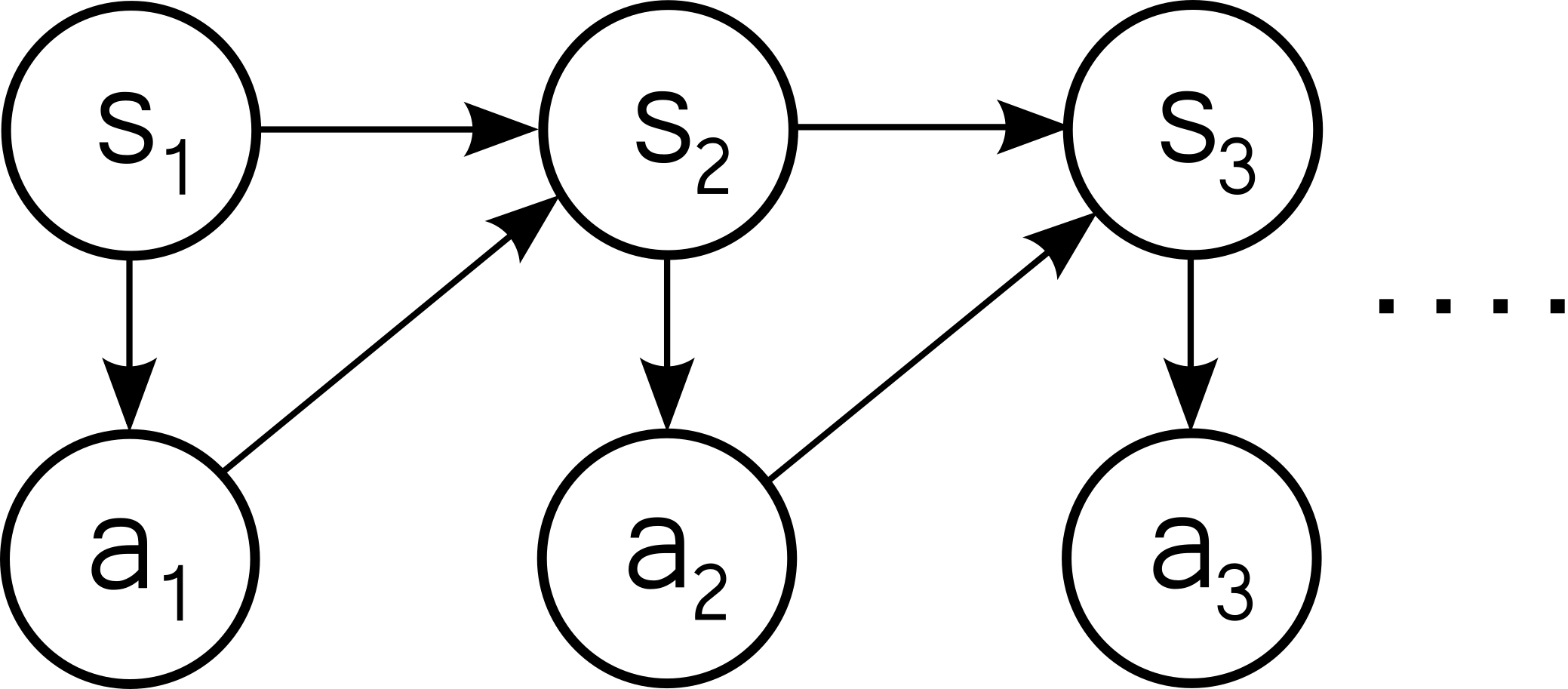

In RL we have an agent that is acting in an environment. We encode all the relevant information about the environment in which the agent is acting into a state vector \(s_t\) which will evolve as the agent interacts with the environment. According to the current state, the agent selects an action \(a_t\) from its policy \(\pi(a_t | s_t)\). After taking this action, the environment will then evolve according to a transition distribution \(P(s_{t+1} | s_t, a_t)\) which depends on both the current state and the action the agent decided to take.

The repeated choice of actions and state transitions can be summarized in the following diagram:

The agent is not just taking random actions, but its intent is to take actions such as to maximize a reward \(r(s_t, a_t)\). The agent receives a reward after each state-action choice. In the setting where the agent interacts with the environment for a total of \(T\) steps, then we would like to choose a policy \(\pi(a_t | s_t)\) such that the agent maximizes the total reward received:

\[J(\phi) = \mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim p_\phi} \left[ \sum_{t=1}^T r(s_t, a_t) \right]\]This expectation is taken with respect to the trajectory distribution which is the distribution over all states and actions induced by the chosen policy \(\pi_\phi\)

\[p_\phi(\tau) = P(s_1) \pi_\phi(a_1 | s_1) \prod_{t=2}^T P(s_t | s_{t-1}, a_{t-1}) \pi_\phi(a_t|s_t)\]Note how we have parameterized the policy, \(\pi_\phi(a_t \vert s_t)\) with parameters \(\phi\).

To help choose good policies, RL uses ideas from dynamic programming, where a value function \(V_t(s_t)\) is introduced which summarizes the expected future reward if the agent were to find itself in state \(s_t\) at time \(t\). This gives a level of foresight which can be used to pick good actions at the current time step \(t\). \(V_t(s_t)\) is defined as

\[V_t(s_t) = \mathbb{E} \left[ \sum_{k=t}^T r(s_k, a_k) \right]\]From this definition, a recursion for the value function can be derived

\[V_t(s_t) = \mathbb{E}_{s_{t+1}, a_t \sim P(s_{t+1} | s_t, a_t) \pi_\phi(a_t | s_t)} \left[ r(s_t, a_t) + V_{t+1}(s_{t+1}) \right]\]This is called the Bellman recursion.

From a backwards recursion to a forwards recursion

The Bellman recursion introduced in the previous section operates in the backwards direction. That is, the value function at time \(t\) depends on the current reward and the future value function at the next step, \(t+1\). If you recall, our eventual aim is to apply these ideas to variational inference in sequential settings where we only move forwards in time. This requires a forwards recursion where a ‘value function’ will depend on the past value function at the previous time step. Keeping with the RL notation for now, I will show how we can use some creative notational rewiring to get a forwards in time recursion.

Our first trick is to consider an anti-causal graphical model for RL. That is, one in which the state at time \(t\), \(s_t\), depends on \(s_{t+1}\) and \(a_{t+1}\). This gives a reverse-time decomposition for the trajectory distribution

\[p_\phi(\tau) = P(s_T) \pi_\phi(a_T \vert s_T) \prod_{t=T-1}^1 P(s_t \vert s_{t+1}, a_{t+1}) \pi_\phi(a_t \vert s_t)\]We now define a new value function that is the sum of previous rewards (instead of future rewards as we had before)

\[V_t(s_t) = \mathbb{E} \left[ \sum_{k=1}^t r(s_k, a_k) \right]\]We then get a recursion for this value function in the forwards direction

\[V_{t}(s_t) = \mathbb{E}_{\pi_\phi(a_t\vert s_t) P(s_{t-1} \vert s_t, a_t)} \left[ r(s_t, a_t) + V_{t-1}(s_{t-1}) \right]\]Connecting the dots

We are now finally ready to see how this can be used to solve our problem from before where we had a term in our sequential variational inference objective that depended on the new variational factors through \(x_{T-1}\) but had a large number of terms from \(T-1\) all the way back to \(1\).

The main idea is to define some ‘rewards’ such that the expected sum of these rewards from \(1\) to \(T\) will be \(\text{ELBO}_T\). Then we can copy over our forwards recursion equation to get a ‘value function’ that summarizes a previous chunk of the ELBO. So overall we will then get an objective that only has 2 terms for every time step rather than \(T\) terms.

We first define our state from RL to be our hidden state in our model \(s_t = x_t\). We then also define our action \(a_t\) to be the hidden state in our model but at the previous time step \(a_t = x_{t-1}\). This seems rather strange but it allows our policy \(\pi_\phi(a_t \vert s_t)\) to correspond to one of our variational factors \(\pi_\phi(a_t \vert s_t) = q^\phi(x_{t-1} \vert x_t)\). Due to this strange definition of states and actions, our state transition function becomes a delta function \(P(s_t \vert s_{t+1}, a_{t+1}) = \delta (s_t = a_{t+1})\). We can now define our new ‘reward’

\[r(s_t, a_t) = r(x_{t}, x_{t-1}) = \log \frac{f(x_t\vert x_{t-1}) g(y_t \vert x_t) q^\phi(x_{t-1})} {q^\phi(x_t) q^\phi(x_{t-1} \vert x_t) }\]With this reward definition, \(\text{ELBO}_T\) becomes just an expected sum of rewards

\[\text{ELBO}_T = \mathbb{E}_{q^\phi(x_{1:T})} \left[ r(x_T, x_{T-1}) + \dots + r(x_1, x_0) \right]\]Our value function is defined as a sum of previous rewards which is actually a chunk of our ELBO

\[V_{t-1} (x_{t-1}) = \mathbb{E} \left[ \sum_{k=1}^{t-1} r(x_k, x_{k-1}) \right]\] \[V_{t-1} (x_{t-1}) = \mathbb{E}_{q^\phi(x_{1:T-2} \vert x_{T-1})} \left[ \log \frac{p(x_{1:T-1}, y_{1:T-1})}{q^\phi(x_{1:T-1})}\right]\]And it still follows the same forward recursion from before

\[V_{t}(x_t) = \mathbb{E}_{q^\phi(x_{t-1} \vert x_t )} \left[ r(x_t, x_{t-1}) + V_{t-1}(x_{t-1}) \right] \label{Vrecursion}\]We now just substitute in \(V_{t-1}(x_{t-1})\) and \(r(x_t, x_{t-1})\) directly into our equation for \(\text{ELBO}_T\)

\[\text{ELBO}_T = \mathbb{E}_{q^\phi(x_T) q^\phi(x_{T-1} \vert x_T)} \left[ r(x_T, x_{T-1}) + V_{T-1}(x_{T-1}) \right]\]We can immediately see how we have solved our issue from before as we now have an objective with only terms on \(x_T\) and \(x_{T-1}\). This will have a constant cost to compute no matter how many observations we have processed previously. All we need to do is keep track of our value function, \(V_T(x_T)\), which we can do through supervised learning. We approximate \(V_T(x_T)\) with \(\hat{V}_T(x_T)\) and learn \(\hat{V}_T(x_T)\) at each time step by solving the following regression problem created from equation \ref{Vrecursion}

\[\underset{\hat{V}_T}{\text{min}} \quad \mathbb{E}_{x_T, x_{T-1}} \left\vert \left\vert \hat{V}_T(x_T) - \left( r(x_T, x_{T-1}) + \hat{V}_{T-1}(x_{T-1}) \right) \right\vert \right\vert_2^2\]In practice, we want to optimize the ELBO with respect to the variational parameters \(\phi\) and not just evaluate the ELBO. We can create similar recursions for \(\nabla_\phi \text{ELBO}_T\). Please see our paper arXiv 2110.12549 for the full details.